Name

A 1644 contract identified a Native American man as “Jaques.”[1] It is uncertain if his Dutch captors assigned this name to him or if this was the name he used for himself.

Origin

Jaques was a Native American man who was captured by the Dutch and given to two Dutch soldiers, who took him to Amsterdam in 1644.[2] The single known record about Jaques does not identify his tribe.

In a draft article about Jaques, George R. Hamell placed Jaques’s capture within the context of Kieft’s War against the Native Americans, during which many were killed and some were captured. Hamell inferred that Jaques was probably a member of a Munsee-Delaware Algonquian-speaking band which inhabited the region around New Amsterdam.[3]

Migration

Jaques was brought to Amsterdam on the ship Graeff Maurits [Count Maurits] in 1644 according to a contract made later that year.[4] The “Voyages of New Netherland” database does not have a ship by that name, but does list the Prins Maurits sailing from Amsterdam to New Amsterdam between 14 January and 15 July 1644.[5] This is probably the same ship, which could have transported Jaques on its return voyage in 1644 that is not documented in the database.

Settlement

Jaques lived in North America, probably in the vicinity of New Amsterdam, until 1644, when he was brought to Amsterdam, the Netherlands.[6]

Biographical Details

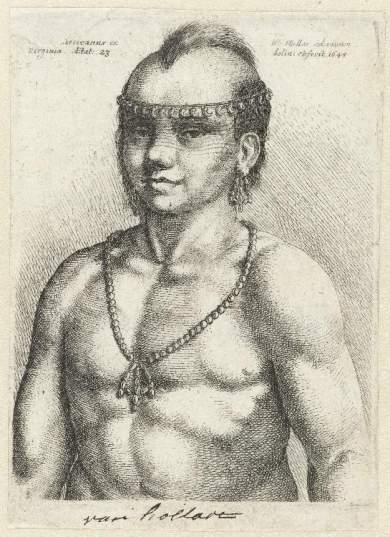

Jaques has been tentatively identified as an American man from Virginia, age 23, portrayed by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1645.[7] In Dutch records of the period, “Virginia” was sometimes used to refer to New Netherland.[8] Prints of this etching can be found in several museums, including the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[9] A version of this print was included in Rev. Johannes Megapolensis’s publication about Mohawk Indians in New Netherland, providing further evidence that this man was from the region around that colony.[10]

If the man in the etching was indeed Jaques, he would have been born about 1622. If Jaques was not the depicted man, it is uncertain how old he was. Not described as a boy, he was probably at least twelve years old; nor was he likely to have been given as a prize if he was an older man. That would put his birthdate between say 1600 and 1632.

The identification of the portrayed man as Jaques is uncertain, since other Native American men were captured and brought to the Netherlands around this time. On 28 October 1644, the Eight Men—residents elected to advise New Netherland governor Willem Kieft—sent a letter to the Amsterdam Chamber of the West India Company describing the conditions in the colony. They wrote how the captured “wilden” [savages or wild ones, a term used for Native Americans] could have been of great service as guides, but were instead given to soldiers and allowed to be taken to Holland, while others were sent to Bermuda as a gift to the English governor.[11] Jaques must have been one of these captives, given to Cock and Ebel as a reward for their military service, consistent with the information in the contract created a month before the Eight men sent their letter.

An anonymous pamphlet confirms the practice of giving Native Americans to soldiers. The pamphlet, published in 1649, criticized the West India Company in the form of a constructed dialogue, allowing the reader to overhear gossip between a skipper, a soldier, and eight others about the situation in New Netherland. Donna Merwick warns that the account was intended to shock the reader, and while believable, it “combined truth and illusion.”[12] In the pamphlet, the skipper described how in April 1644, the Dutch arrested seven Native Americans who were falsely accused of theft. Fifteen or sixteen soldiers went into the cellar where the Native Americans were held, and killed three of them. Two more men died on the way back to New Amsterdam, after soldiers tied ropes around their necks and dragged them behind the boat. When the soldiers could not agree who would receive the survivors as bounty, Kieft gave the two remaining men to the soldiers to torture and kill. One man was forced to perform a native dance while he was being gutted until he dropped dead. The other had his skin cut to ribbons and his genitals cut off before he was beheaded.[13] These events supposedly took place around the time Jaques was captured and brought to Amsterdam. The account, though perhaps not accurate in details, exemplifies the humiliation and violence Native Americans endured in captivity.

Jaques died at an unknown date after 3 September 1644.[14] In his study of New Netherland, Jaap Jacobs explained it is unlikely that Jaques would have lived long afterwards, as most Native Americans who were brought to Europe quickly succumbed to diseases for which they lacked immunity.[15]

Education

Captured during Kieft’s War with tribes in the vicinity of New Netherland, Jaques would probably have spoken the Munsee language. One of his captors, Pieter Ebel, later was an Algonquian interpreter and may have known the Munsee language spoken around New Amsterdam.[16]

Jaques did not speak Dutch by 3 September 1644. The men who held him in captivity promised to teach him that language,[17] but it is uncertain that they ever did.

Enslavement

Jaques was captured during a series of violent encounters between the New Netherland colony and Native American tribes between 1643 and 1645. These events became known as Kieft’s War, after governor Willem Kieft who ordered attacks on Native American tribes.[18]

Jaques appears in a single record, created before notary Pieter van Velsen in Amsterdam on 3 September 1644. On that date, Pieter Cocq (usually known as Cock) from Olburg and Pieter Evel (usually: Ebel) from Gustero in Meckelenburg entered into an exclusive contract with Harmanus Meijer to put Jaques on display for money. Cock and Ebel explained they had both been soldiers in the service of the West India Company. The governor of New Netherland had given them a “wilde Indiaen” [savage Indian] named Jaques in free ownership. The soldiers brought Jaques with them when they sailed back to Amsterdam on the ship Graeff Maurits [Count Maurits] in 1644.[19]

The parties agreed that Harmanus Meijer would undertake the work of exhibiting Jaques. In return, Meijer and his wife would receive half of the profits. Meijer would be responsible for providing access to Jaques and collecting the money in a box from which expenses would be covered. Both contracting parties committed to promoting the exhibition and assisting each other where necessary. Considering that slavery was outlawed in the Netherlands, they had to promise to teach Jaques the Dutch language in order to instruct him in Christianity, Christian virtues, and morals. In addition, Jaques was to receive food and clothing in line with what was customary for a servant in the Netherlands. If Cock or Ebel were to leave Amsterdam, they would leave Jaques with Meijer, in return for a present at Meijer’s discretion.[20]

Slavery was illegal in the Netherlands outside the colonies. The Amsterdam city ordinance of 1644 stipulated that “In the city of Amsterdam and its jurisdiction, all men are free, and not slaves. All slaves that are brought within this city or its jurisdiction, are free and outside the power and authority of their masters and mistresses; and if their masters or mistresses want to keep them as slaves, and force them to serve against their will, these persons may subpoena their masters and mistresses before the court, and make them declare them legally free.”[21] Although the contract acknowledged that slavery was outlawed in the Netherlands and made stipulations to treat him as a servant, Jaques was not a party in the contract; de facto treating him as an enslaved man in Amsterdam. Unable to speak Dutch, Jaques would not have been aware of the city ordinance and the rights he had under Dutch law.

Occupation

Jaques’s occupation prior to his captivity is unknown. He was exhibited for money after he was brought to the Netherlands in 1644.[22]

Church Membership

The men who planned to exhibit Jaques promised to instruct him in Christianity.[23] This appears to have been added to the contract to show that Jaques was treated like a servant rather than a slave, to make the transaction legal in the Netherlands. It does not mean he was actually taught, or that he converted to Christianity.

Associations

Support New Netherland Settlers

Help us support New Netherland Settlers and further more research and additional sketches.

Do you have a New Netherland ancestor that should be included or other information to contribute to the initiative? Please email development@nygbs.org with the subject line "NNS Information," and we will follow up with you.

Jaques was awarded to Pieter Cocq from Olburg and Pieter Evel from Gustero in Meckelenburg. George R. Hamell identified Pieter Cocq as Pieter Cock from Ålborg, Denmark, who had been in the Netherlands by 1634 and fought as a soldier for the West India Company during Kieft’s War in the early 1640s. He returned to New Amsterdam by 1649.[24] He identified Pieter Evel as Peter Ebel from Güstrow, now located in Mecklenberg-West, Pomerania in Germany, whose presence in New Netherland had not been documented before his appearance in this contract. Ebel was back in New Amsterdam by 1650.[25] Since both men returned to New Netherland, their active involvement in exhibiting Jaques in Europe lasted no more than five years.

Harmanus Meijer, the other contracted party, was probably the 25-year-old Harman Meijer from Hamburg who requested proclamations to marry the 22-year-old Sophia Sasbout from Amsterdam on 10 May 1641.[26] As Harmanus Meijer, he had children Cattarijn and Sasbout baptized in the Lutheran church of Amsterdam on 9 December 1642 and 8 September 1644, respectively.[27] He had a German background like Ebel, was married, and was in Amsterdam at the right time to enter into a contract with them.

Literature

Hamell, George R. “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland.” Albany, New York. November 1996. https://www.academia.edu/10778527/JAQUES_A_MUNSEE_FROM_NEW_NETHERLAND.

This draft article discusses Jaques in the wider context of Kieft’s War and the history of Native Americans being sent to Europe. It provides biographical information about Pieter Cock and Pieter Ebel and explains why they were awarded Jaques for their military service.

Jacobs, Jaap. Een Zegenrijk Gewest: Nieuw-Nederland in de Zeventiende Eeuw. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Prometheus-Bert Bakker, 1999. pp. 333–334.

This Dutch version of Jaap Jacobs’s study of New Netherland includes a discussion of Jaques. This version cites the original Dutch sources where available.

_____. New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America. Leiden, Netherlands and Boston, Massachusetts: Brill, 2005. pp.397–398. This English version of the previous book cites published translations where available.

Citations

[1] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644, in Pieter van Velsen, notary (Amsterdam), protocol of minutes and copies, 11 August 1641–30 December 1644, fol. 83v–85r; finding aid and images, Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarchief (https://archief.amsterdam/inventarissen/file/5b38c12d-fc2d-8ee2-6684-149f5d29d533); citing call no. 1781, Record Group 5075, Notarial Archives of Amsterdam, Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. George R. Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland” (Albany, New York, November 1996), 16, https://www.academia.edu/10778527/JAQUES_A_MUNSEE_FROM_NEW_NETHERLAND.

[2] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[3] Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland,” 14.

[4] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[5] Julie van den Hout, “Voyages of New Netherland,” New Netherland Institute (https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/digital-exhibitions/voyages-of-new-netherland : accessed 16 October 2024), database, voyage v_091.

[6] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[7] Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland.”

[8] For example, in his history of remarkable events in the 1620s, Nicolas Jansz. van Wassenaer called referred to “de Colonie in Virginia, by ons nieuw Nederlandt ghenaemt” [the colony in Virginia, called New Netherland by us]. Nicolaas Jansz van Wassenaar, t’Neghenste deel, of t’ vervolgh van het Historisch verhael aller gedenckwaardighe geschiedenissen, die [...] van april des jaers 1625, tot october toe, voorgevallen syn (J. Ianssen, 1625), 40.

[9] Wenceslaus Hollar, “Unus Americanus ex Virginia, Aetat: 23,” print, 1645; imaged, Rijksmuseum (http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.32828); citing object RP-P-OB-11.592, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Wenceslaus Hollar, “Unis Americanus ex Virginia,” print, 1645; imaged, The Met (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/361737); citing accession no. 56.507.9, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[10] Johannes Megapolensis, Een kort ontwerp, van de Mahakvase Indianen, haer landt, tale, statuere, dracht, godes-dienst ende magistrature. Aldus beschreven ende nu kortelijck den 26. Augusti 1644. opgesonden uyt Nieuwe Neder-lant. Door Johannem Megapolensem juniorem, perdicant aldaar. Mitgaders een kort verhael van het leven ... der Staponjers, in Brasiel (Alkmaar, Netherlands: Ysbrant Jansz. van Houten, 1645).

[11] Cornelis Melijn and others, letter to the directors of the Amsterdam Chamber of the West India Company, 28 October 1644, copy, in records regarding reports about the situation in New Netherland and the procedures against Cornelis Melijn, 1649–1650, with earlier records, 1642–1648; citing call no. 12564.25, Record Group 1.01.02, Archives of States-General, Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands.

[12] Donna Merwick, The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian Encounters in New Netherland (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 151–169.

[13] I.A.G.W.C., Breeden-raedt aende Vereenichde Nederlandsche provintien: Gelreland, Holland, Zeeland, Wtrecht, Vriesland, Over-Yssel, Groeningen (Antwerp: Francoys van Duynen, 1649), C 3.

[14] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[15] Jaap Jacobs, The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2009), 211–212.

[16] Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland,” 30.

[17] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[18] Jacobs, The Colony of New Netherland, 76–80.

[19] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[20] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[21] Translated quote from Gerard Rooseboom, Recueil van verscheyde keuren, en coustumen: mitsgaders maniere van procederen, binne der stede Amsterdam (Gerrit Jansz, 1644), 186.

[22] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[23] Contract between Pieter Cocq, Pieter Evel, and Harmanus Meijer about exhibiting Jaques, 3 September 1644.

[24] Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland,” 17–22.

[25] Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland,” 22–31.

[26] Marriage proclamations for Harman Meijer and Sophia Sasbouts, 10 May 1641, in Amsterdam, marriage proclamations from the church, 1641, p. 269; index and images, Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarchief (https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/deeds/f20532ec-aedd-4fb1-8f12-ccf4192322a6); citing call no. 455, Record Group 5001, Archives of the Civil Registration: Baptism, Marriage, and Burial Books of Amsterdam, Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

[27] Baptism of Cattarina Meijer, 9 December 1642, in Evangelical-Lutheran Church (Amsterdam), baptismal register 1641–1647, pp. 94; index and images, Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarchief (https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/deeds/773dabb3-7519-4988-8e21-bc77b8352eaf); citing call no. 141, Record Group 5001, Archives of the Civil Registration: Baptism, Marriage, and Burial Books of Amsterdam, Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Also, baptism of Sasbout Meijer, 8 September 1644, in Evangelical-Lutheran Church (Amsterdam), baptismal register 1641–1647, p. 209; index and images, Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarchief (https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/deeds/01157360-15cc-4b61-9885-7616b2fc7e29).

New Netherland Settlers is made possible by donations from organizations and individuals. For more information on how to support the project, email development@nygbs.org.