Jan (or John) Harberdinck (b. circa 1640s; d. 1722/24) is remembered today as a major benefactor of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of the City of New York, more familiarly known as the Collegiate Church.

He came to New Amsterdam from Bocholt (spelled Boeckholdt in his marriage record)—in Westphalia, Germany, close to the border with the Netherlands.1 In his will he mentions a number of relatives in the Netherlands. The surname is spelled in various ways (Harberdinck, Harperding, Harpending, etc.), which seem confusing, but in fact the forms are not really as different as they look, since in the Dutch spelling of the time, b/p, er/en, and ing/inck can be phonetic equivalents. The spelling “Harberdinck” is used here because it appears in the text and signature in his will.

He appears—as Jan Herberding—on the list of members who joined the Dutch Church on April 6, 1664.2 Harberdinck’s marriage intention is dated December 8, 1667, and the marriage took place on December 25, 1667.3 The bride, Maijken (a form of Maria) Barents, is recorded as from Haerlem (presumably the city in the Netherlands, as opposed to New Netherland). This was the first marriage for both the bride and the groom.

Of this marriage, one child is recorded: Assuerus, baptized November 18, 1668, in the Reformed Dutch Church.4 This name is a form of the biblical Asuerus (in the Vulgate, or Latin Bible); Ahasueros or Ahasveros in the Statenbijbel (Dutch); and Ahasuerus in the King James Bible (Ezra iv. 6; Esther i. 1). The child seems to have died at an early age, since he does not appear again in the records, and Harberdinck in his will mentions no children of theirs as heirs.

Jan Harberdinck was by trade a leather-worker (tanner and currier) and shoemaker. In 1674, when for taxation purposes a census was made “of the best and most affluent inhabitants of this city,” Harberdinck was listed with property valued at 2,000 guilders, a substantial sum for the time.5 At this period he and his wife were witnesses to many baptisms in the Dutch Church, a circumstance that shows they were well-regarded in the community. He also held offices in local government and in the Church (deacon and elder).

Harberdinck was chosen a member of the tanners’ guild on August 25, 1676.6 Because the chemical processes involved in tanning were polluting and gave off noxious odors, activities of tanners were normally confined to relatively remote areas of the city. In 1691, a group of leather-workers, including Harberdinck, jointly purchased for their use an area of outlying land that became known as the Shoemakers Pasture (or Field), consisting of about 16 acres beyond Wall Street, which at that time marked the approximate northern limit of the city.

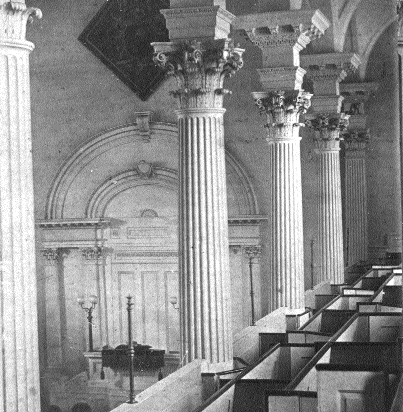

the North Gallery. From a stereo photo by E. Anthony,

from series, "The Fulton Street Prayer Meeting, Illustrated"

(1857), no. 6, "The North Church."

On April 8, 1722, Harberdinck wrote his will. Within two years the will was probated, February 7, 1723, Old Style (1724, New Style).7 There is no record of his exact date of death. From the date of his marriage, 1667, one can estimate that he was born around the 1640s, and would have been about 80 years old when he died.

The testator, in addition to making bequests to family members and friends in the Netherlands and in New York, provides a major legacy to the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church: his share in the Shoemakers Pasture. The property as a whole had been divided into 164 numbered lots; 35 of these, itemized in the will, were owned by Harberdinck. He stipulates that this property is to go to the Church after the decease of his wife Maijken, and that the income is to be used by the Church for the payment of the yearly stipend of the minister or ministers. He further specifies that the land is to be held indefinitely by the Church for this purpose. In later years, when the area became a prime commercial location, especially the block bounded west by Broadway and east by Nassau Street, north by Fulton Street and south by John Street (named after Jan—or John—Harberdinck), the Church would derive a generous income from the bequest.

In recognition of this important benefaction, after Harberdinck’s death a hatchment was hung in the Garden Street Church (opened in 1693), where there were several memorials of this kind; also, armorial designs (commemorating members who were elders and magistrates) were burned into the glass windows by the artist Gerard Duyckinck. The term “hatchment” refers usually to a lozenge-shaped panel painted with a coat of arms, and hung over or near a tomb or memorial to a deceased person. William J. Hoffman, in An Armory of American Families of Dutch Descent, notes that the custom of hanging memorial hatchments in churches was well known in the Netherlands.8

The Garden Street Church was on the north side of what is now Exchange Place, with the tower facing west toward Broad Street; toward William Street on the east the church had an apse in the form of a half octagon. As the city grew, the congregation built an additional church (1726–1731) further uptown, on the east side of Nassau Street, above Little Queen (later Cedar) Street, with the tower facing northward toward Crown (later Liberty) Street. This was at first called the New Church. Eventually a third church was built, called the North Church, at the northwest corner of Fair (later Fulton) Street, fronting on William Street; dedicated May 25, 1769. The former New Church then became known as the Middle Church (in 1844 the building was sold to the Post Office and demolished in 1882), and the Garden Street Church was then called the South Church (burned in 1835).

Upon completion of the North Church in 1769, the consistory ordered that the coat of arms of John “Harpending” in the South Church, “should be copied in an appropriate manner, and the copy hung in the North Church above the pulpit.”9

End Collegiate Church; photo by Jim

Philbin, Collegiate Church (2010).

In the North Church, the panel showing the Harberdinck arms was a large diamond with right-angled corners; it was placed in perhaps the most conspicuous point in the interior, high in the center of the wall directly over the pulpit, where it would immediately be seen by all upon entering the church, and where it would be contemplated by all listening to the sermon.10 Its relevance was that the church stood on a portion of the land from Harberdinck’s bequest. The North Church remained in use until 1875, when it was demolished.11 After this date, services for the immediate neighborhood continued in the North Church Chapel, at 113 Fulton Street, where the Fulton Street Prayer Meetings, begun in 1857, continued to be held.

In later years the original hatchment—painted on canvas stretched over a wooden frame—was kept in storage at the present Middle Collegiate Church, built in 1892 at 112 Second Avenue, near Seventh Street. But the canvas eventually deteriorated beyond repair, and today all that survives of the original are a few fragments. However, there are several illustrations of the coat of arms, so there is little doubt about its appearance.12

On an azure field, the charge is a currier’s beam, a large and important tool of the leather-worker’s trade. The crest is in keeping with thecharge: a currier’s knife, used for paring leather. The Latin motto, Dando conservat expresses a witty paradox: “by giving he keeps.” Thomas De Witt in his historical Discourse (1857) paraphrases this as: “the best means of securing and giving permanence to our property is to devote it to beneficent uses.”13

De Witt raises the interesting point of whether the coat of arms was hereditary: “A doubt has arisen in my mind, whether this was originally a real coat of arms, or whether it was a design procured by the Church to commemorate his benefaction.” De Witt adds: “It is a doubt which can not now well be solved.”14 But it would seem that the question is solved fairly certainly in favor of De Witt’s suggestion by the fact that there is no record of these arms having been used by Harberdinck’s ancestors, or even by John Harberdinck himself. The arms, instead of celebrating the military exploits of a noble lord, reflect the hard manual work of a successful tradesman. One might say that this is very much in keeping with the changing times, in which business was the path to wealth, and consequently to social and political influence.

Notes

1 David M. Riker, Genealogical and Biographical Directory to Persons in New Netherland from 1613 to 1674, 4 vols. (Mechanicsburg, Pa., 1999), vol. 2, unpaged, under Harpendinck notes his arrival in 1663 on the ship de Statyn. The list is given by E. B. O’Callaghan, in The Documentary History of the State of New-York, vol. 3 (Albany: Weed, Parsons, & Co., 1850), p. 41, but the entry there is for arrival on the Stetin of “Grietje Hargeringh, Jan Hargeringh, from Newenhuys”—a different family.

Rosalie F. Bailey, “Emigrants to New Netherland,” NYG&B Record, vol. 94, no. 4 (October 1963), lists this group as arrivals in the Hope, April 8, 1662, with the name “Gerrit Hargerinck,” from “Nieuwenhuys,” who went to Fort Orange (i.e. Albany).

2 “Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in the City of New York, Church Members’ List,” NYG&B Record, vol. 9, no. 2 (April 1878), p. 77 (ms. p. 516). Herberdinck in his will mentions his “kinsman,” “John Harberdinck Junr.” who was (as implied by “Junr.”) considerably younger; he married in 1716 (p. 124 of RDC Marriages; see note 3).

3 Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in New Amsterdam and New York: Marriages from 11 December, 1639 to 26 August, 1801, edited by Samuel S. Purple (New York: NYG&B Society, 1890), p. 32 (ms. p. 617).

4 Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in New Amsterdam and New York: Baptisms from 25 December, 1639 to 27 December, 1730, edited by Thomas Grier Evans (New York: NYG&B Society, 1901), p. 92 (ms. p. 348); the printed record gives the name as “Assudius,” a misreading of the ms.

5 Ecclesiastical Records State of New York, published under supervision of Hugh Hastings, edited by Edward T. Corwin, 7 vols. (Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1901–1916), vol. 1, p. 642. Of 62 names on the list, the highest amounts are for: Fredrick Philipsen, 80,000; Cornelius Steenwyck, 50,000; Nicolaes de Meyer, 50,000; Olof Stevense van Cortlandt, 45,000; and Jeronimus Ebbingh, 30,000. The great majority are between 1,100 and 10,000.

6 Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York 1675–1776, 8 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1905), vol. 1, pp. 21–22, 24.

7 Recorded at New York City Wills, Liber 8, pp. 440–446 (old liber), 509–517 (new liber), probated February 7, 1723 O.S. (1724 N.S.). Abstract in Collections of the New-York Historical Society

for the Year 1893, vol. 26 of Collections (New York: Printed for the Society, 1894), vol. 2 (1708–1728) of Abstracts of Wills, pp. 283–285.

8 William J. Hoffman, An Armory of American Families of Dutch Descent, edited by F. J. Sypher (New York: The NYG&B Society, 2010), pp. 367–368. Hoffman’s information was incomplete when he added that Harberdinck’s hatchment was the only instance he knew of this practice being carried over into New Netherland. Thomas De Witt, in A Discourse Delivered in the North Reformed Dutch Church (Collegiate), in the City of New-York, on the Last Sabbath in August, 1856 (New York: Board of Publication of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church, 1857), p. 27, mentions that there were other hatchments at the Garden Street Church, as well as arms on the windows.

9 Consistory minutes, March 20, 1769, quoted in Ecclesiastical Records, vol. 6 (1905), p. 4139.

10 On the back of the stereo view reproduced with this article, is the following text: “Interior view of Pulpit and the Harpending tablet from the North Gallery. A tablet containing a Coat of Arms commemorative of Mr Harpending at this day, hangs conspicuously on the wall above the pulpit. On the scroll is inscribed the admirable motto, Dando Conservat; conveying the sentiment

that the best mode of securing and giving permanence to one’s property is to devote it to charitable uses.” Underneath is written: “Published by E. Anthony, Broadway, New-York.” As of 1859

Anthony’s studio was at 501 Broadway; as of 1886 he was at 591 Broadway.

11 When the North Church (where Columbia’s commencement took place in 1809) was demolished in 1875, the original wroughtiron gates were acquired by Abraham Hewitt and donated to Columbia College (then at 49th Street and Madison Avenue); they were moved when Columbia established the Morningside Heights campus (opened in 1897), where they now stand on either side of

the entrance to St. Paul’s Chapel.

12 Early illustrations of the Harberdinck arms: De Witt, Discourse (1857), facing p. 34, and see p. 96; History of the School of the Collegiate Reformed Dutch Church in the City of New York, from

1633 to 1883, 2nd ed. (New York: The Consistory of the Church, Printed by the Aldine Press, 1883), p. 276; terra cotta relief on the facade of West End Collegiate Church, West End Avenue and 77th

Street (1892).

13 De Witt, Discourse, p. 33.

14 De Witt, Discourse, p. 33.

by Francis J. Sypher Jr.

Originally published in The New York Researcher, Spring 2011

© 2011 The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society

All rights reserved.